Obstacles to delivering interdisciplinary dental care

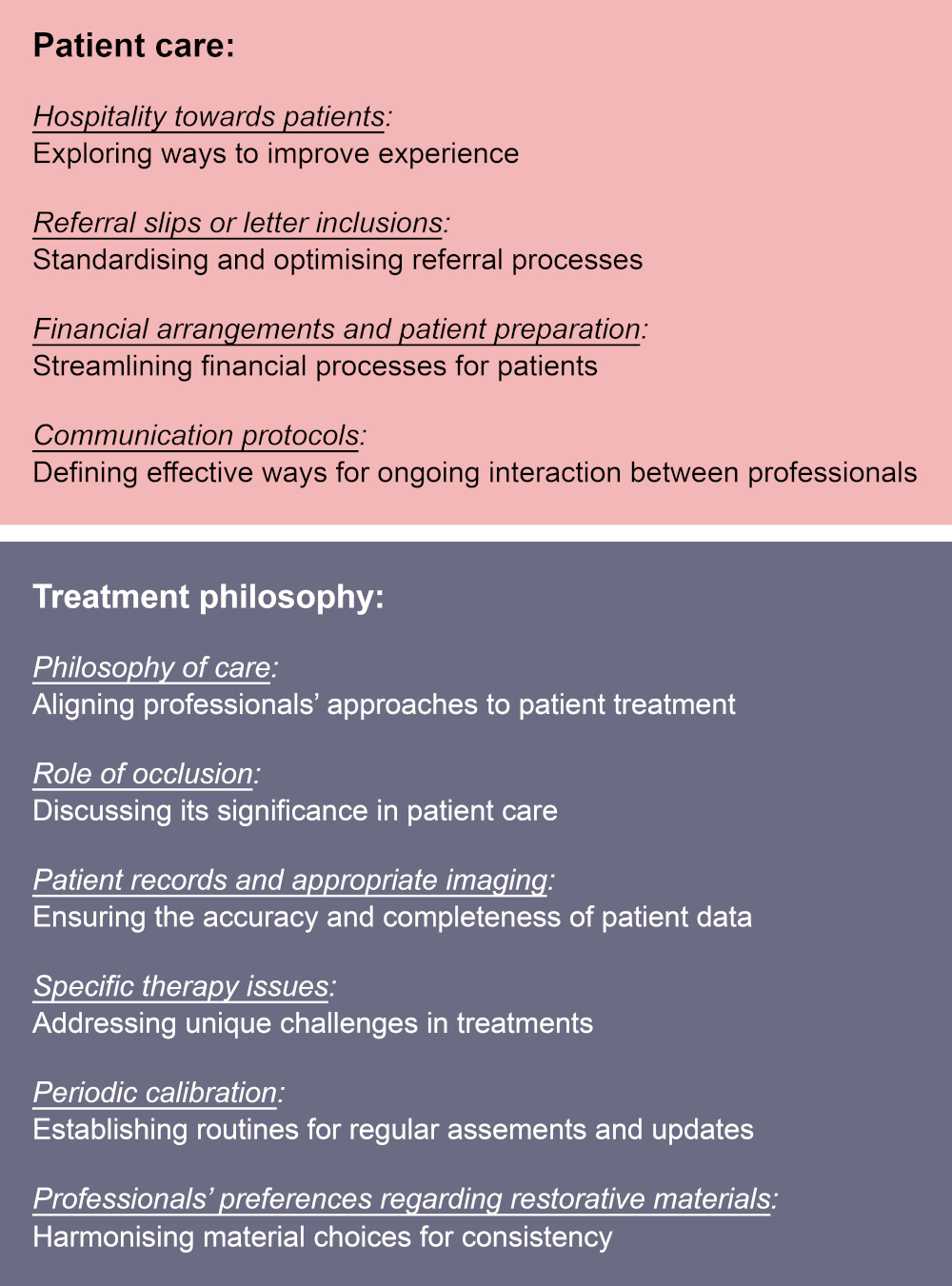

Despite the significant advantages of delivering dental care through a collaborative interdisciplinary approach, most dental care is delivered according to uni-disciplinary or multidisciplinary approaches. Anecdotally, when dental professionals are asked about their reluctance to adopt an interdisciplinary approach to dental care, their responses generally fall into two categories: the complexity of delivering interdisciplinary care—essentially not knowing where to start—and the time-consuming nature of communication within an interdisciplinary team.

To address these challenges, a systematic framework—essentially an operating system for interdisciplinary care—is necessary. The core advantages of this approach are the consistency and standardisation of best practices, as well as the optimisation of treatment efficiency and resource utilisation.

A four-step framework for developing an interdisciplinary treatment plan

To overcome complex issues, a set of guidelines is essential for tackling the problem consistently.³ These guidelines help in formulating a clear plan and resolving each issue by breaking it down into simpler, manageable components.

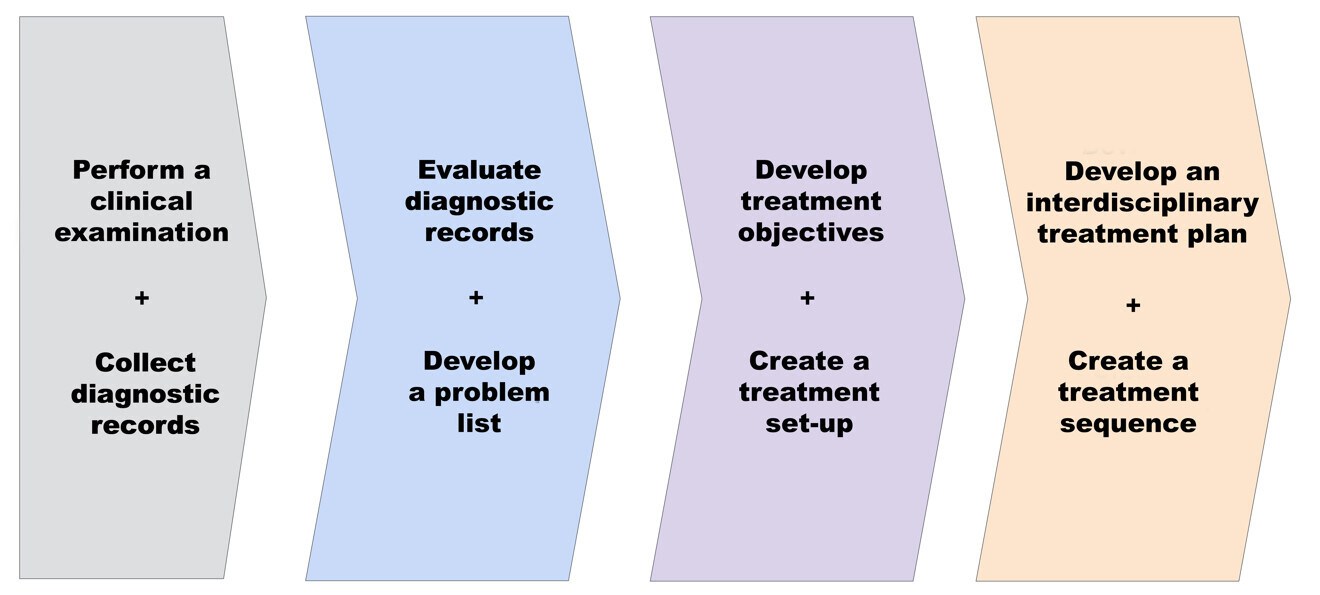

An interdisciplinary treatment planning framework offers a comprehensive structure that encompasses various methodologies, techniques and processes. Essentially, it acts as an operating system guiding practitioners through each step—from collecting information and analysing records to developing problem lists and treatment objectives (Fig. 1). Finally, it aids in formulating an interdisciplinary plan and determining the sequence of treatment. This framework simplifies the process and helps practitioners develop muscle memory as they practise delivering interdisciplinary dental care.

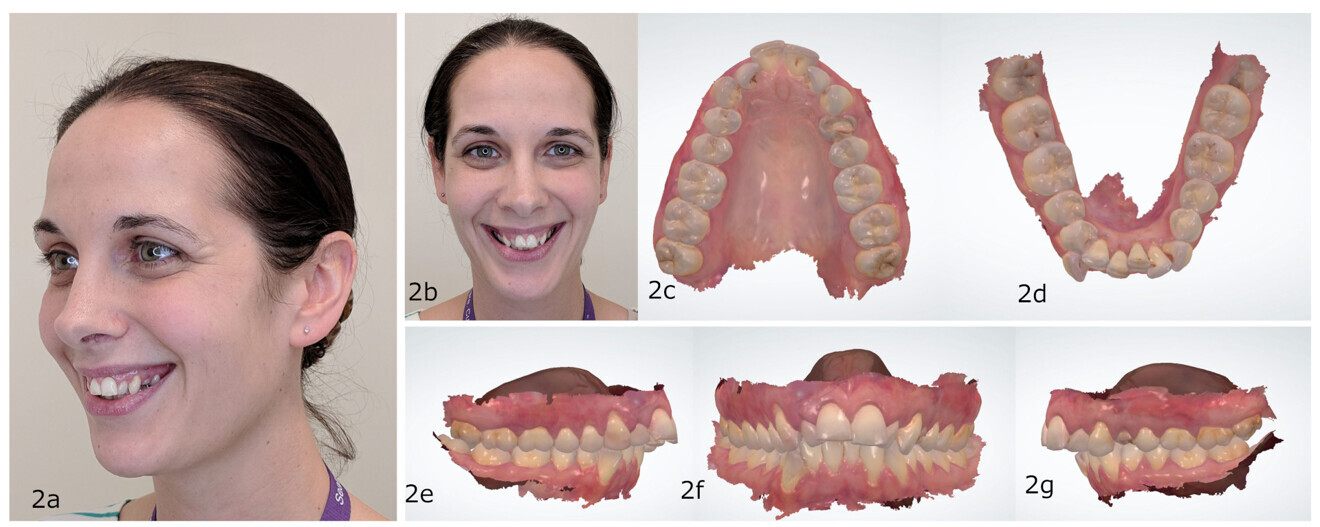

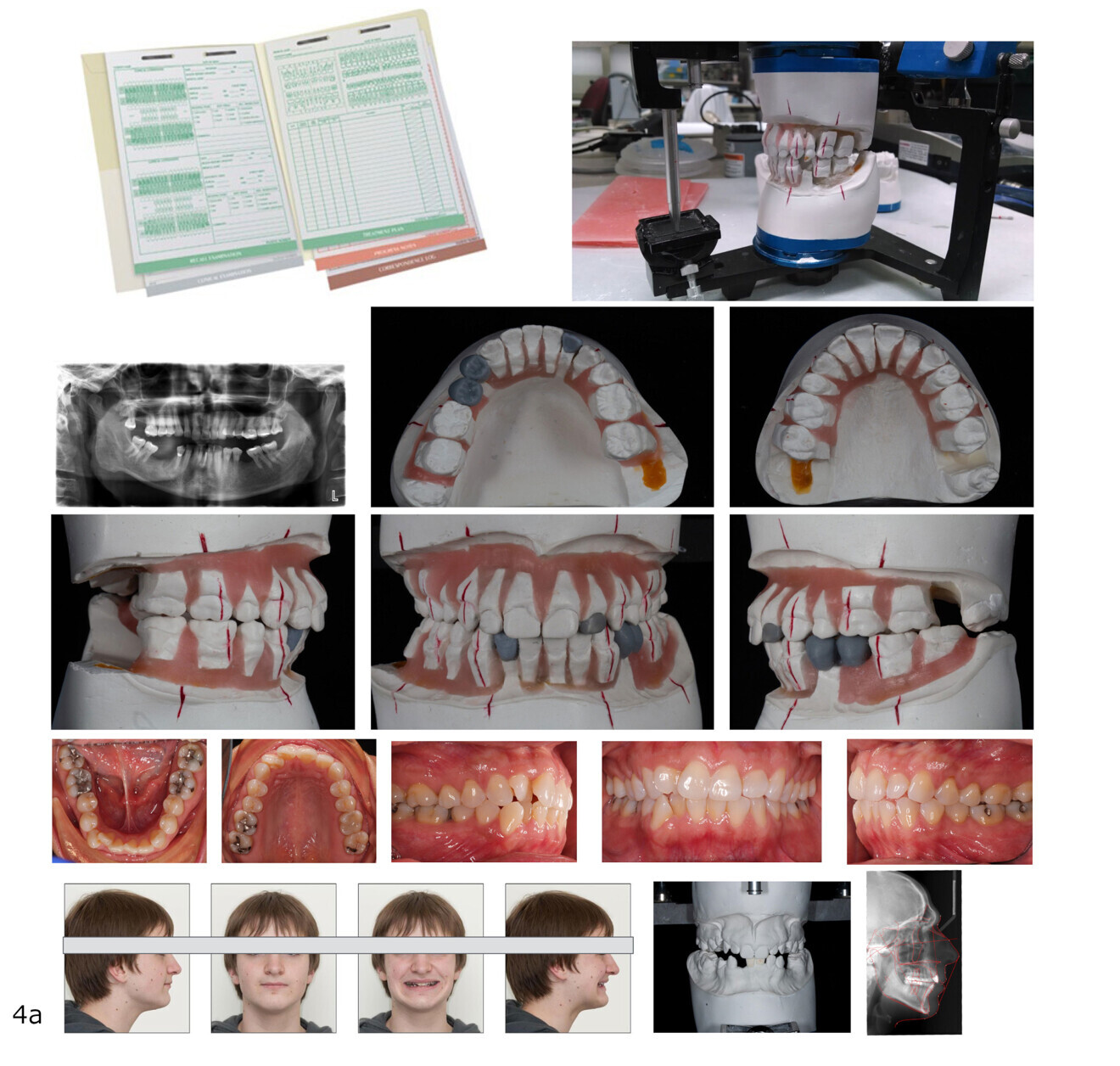

The first step of interdisciplinary treatment planning begins with a clinical examination to collect both subjective and objective information. This includes acquiring diagnostic records such as 3D dental models, radiographs, questionnaires, and intra-oral and extra-oral photographs. Subjective information encompasses the patient’s medical and dental history, as well as social history (e.g. family structure and dynamics, distance to commute for care and level of interest and engagement). At this stage, it is also vital to assess the patient’s perceptions and expectations and conduct an objective assessment.

The clinical examination encompasses both extra-oral and intra-oral assessments of the patient. These assessments should take into account all three planes of space: anterior–posterior, transverse and vertical. During the clinical examination, it is essential to document facial and skeletal patterns, as well as collect smile arc records. Additionally, a thorough periodontal evaluation, an assessment of the patient’s restorative status (including aesthetic and functional occlusion) and a temporomandibular joint evaluation should be performed. The periodontal examination should include an assessment of gingival type, bone topography, oral hygiene, gingival aesthetics (including display, colour, contour and papillary form), probing depths, recession and furcation involvement—including horizontal bone loss. Restorative assessments should cover all aspects of the occlusion: contacts, guidance, mobility, functional mobility, tooth position (including rotation and tipping) and any existing restorative work or needs, such as caries. This comprehensive approach ensures a detailed and accurate evaluation of the patient’s overall oral health.

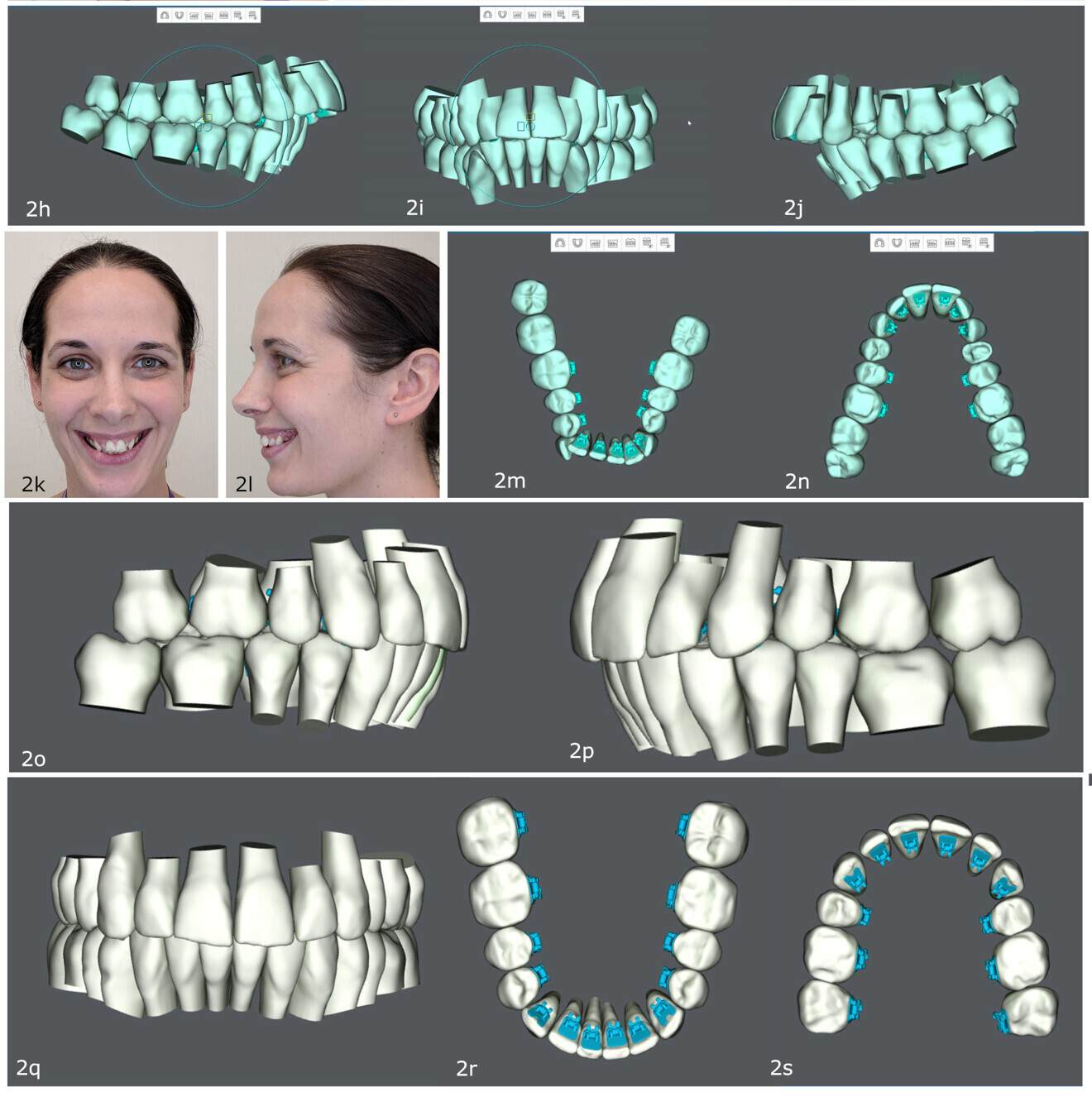

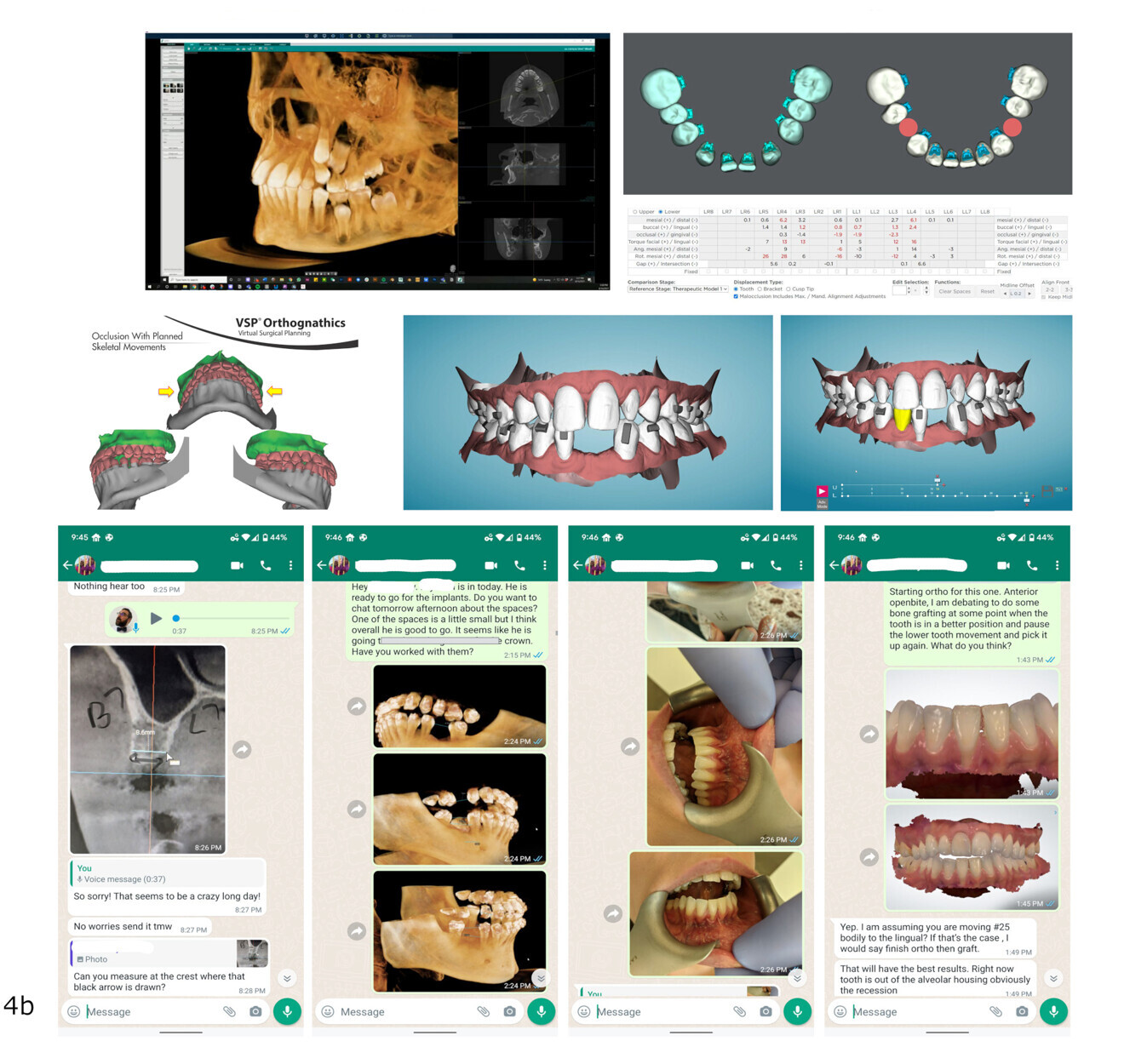

The second step involves evaluating the diagnostic records and clinical examination information to develop a comprehensive problem list. This evaluation should involve analysis of all diagnostic records, such as 3D scans and radiographs, video records (e.g. smile analysis), 2D photographs, questionnaires (e.g. nutrition or sleep evaluations) and reports (e.g. sleep reports and physician’s letters). To ensure thoroughness and consistency, it is advisable to use a standardised template for this step.⁴ This approach helps to avoid overlooking information and helps to maintain consistency over time, facilitating a more accurate and reliable development of the problem list.

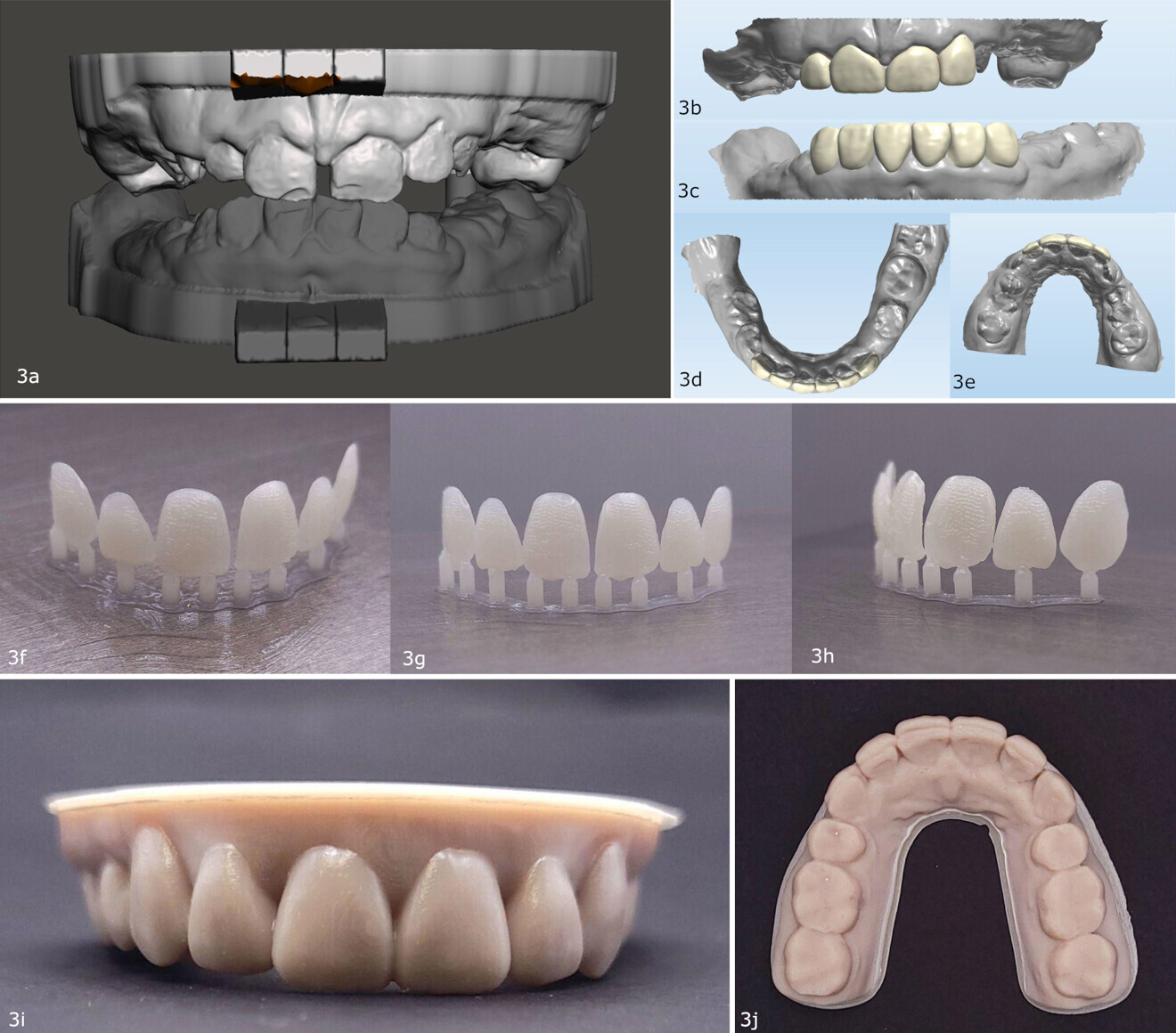

The third step involves using the problem list to establish treatment objectives that aim to completely or partially address the identified issues. As part of this step, a treatment simulation should be conducted to evaluate the feasibility of the proposed treatment objectives. For example, one might consider how much mandibular anterior intrusion is required to level the mandibular arch completely and whether this level of intrusion is biologically achievable and predictable, or one might determine how much space is necessary to restore severely worn maxillary anterior teeth. By carefully examining these factors through treatment simulations, clinicians can ensure that the treatment objectives are realistic and achievable.

The fourth step entails formulating the treatment plan and creating a treatment sequence with clear assignment of treatment objectives to be addressed by the respective members of the interdisciplinary team. When developing a treatment plan, one ought to clearly define the differences between normal and ideal conditions, appreciate dental and skeletal compensations, and recognise the limitations of all procedures and techniques in an interdisciplinary treatment plan.⁵ When finalising the treatment plan, the financial aspect of care must be considered. A practical and predictably successful interdisciplinary treatment plan can be developed around a compromised treatment, for example leaving an adult patient in posterior crossbite with a functional occlusion.

Following these four steps helps providers to develop a clear and structured approach to interdisciplinary treatment, regardless of the complexity of care. For more detailed information on this process, please refer to Nelson et al.⁴

Austria / Österreich

Austria / Österreich

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bulgaria / България

Bulgaria / България

Croatia / Hrvatska

Croatia / Hrvatska

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

France / France

France / France

Germany / Deutschland

Germany / Deutschland

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Hungary / Hungary

Hungary / Hungary

Italy / Italia

Italy / Italia

Netherlands / Nederland

Netherlands / Nederland

Nordic / Nordic

Nordic / Nordic

Poland / Polska

Poland / Polska

Portugal / Portugal

Portugal / Portugal

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Slovenia / Slovenija

Slovenia / Slovenija

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Spain / España

Spain / España

Switzerland / Schweiz

Switzerland / Schweiz

Turkey / Türkiye

Turkey / Türkiye

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

International / International

International / International

Brazil / Brasil

Brazil / Brasil

Canada / Canada

Canada / Canada

Latin America / Latinoamérica

Latin America / Latinoamérica

China / 中国

China / 中国

India / भारत गणराज्य

India / भारत गणराज्य

Pakistan / Pākistān

Pakistan / Pākistān

Vietnam / Việt Nam

Vietnam / Việt Nam

ASEAN / ASEAN

ASEAN / ASEAN

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Middle East / Middle East

Middle East / Middle East

Thanks so much, Rooz for a comprehensive and well structured presentation on the values of interdisciplinary collaboration. You have motivated me to reconfigure my practice protocols and connections with referring Drs.